The notion that resistance to the ‘educational-industrial complex‘ is futile is itself hard to resist. I believe, however, that we have a responsibility to our students, employees and colleagues to respond in a meaningful way, rather than just shrugging our shoulders while mumbling something about 21st century skills. And so, instead of “adopting a stance of weary resignation or uncomfortable compliance” (Selwyn 2014), I proposed during my English Conference 2015 session the following five-point plan.

1. A 2-year moratorium on ‘innovation’ in education

I was only partly joking with this suggestion but I was completely sincere in my call for something like the ‘London Statement’ in relation to the issues and practices discussed in this series of posts. I suggested that concerned delegates meet during the lunch break to draft a ‘Brisbane Statement’. It didn’t happen but perhaps we can build momentum towards a ‘Hobart Statement‘?

2. Read

Selwyn’s book is a great place to start, particularly for a brilliantly-written analysis of the ideological nature of educational technology. It’s rather pricey though, even in ebook format.

Schneier’s book, published in January this year, is good for understanding the ‘hidden battles to collect our data and control our world’. It’s technical but still pretty accessible to most readers, I think.

Brunton and Nissenbaum’s book, published just last month, is based on the assumption that ‘opting out’ of technologies that collect and share our data is not practical or desirable for many of us. It’s a very concise discussion of various responses to data collection and their ethical dimensions.

3. Ask critical questions

Selwyn (2014) argues that we should move away from

asking ‘state-of-the-art’ questions about technology, towards questions that can be described as being concerned with the ‘state-of-the-actual’. In other words, education technology scholarship should look beyond questions of how technology could and should be used, and instead ask questions about how technology is actually being used in practice.

So, when we find new technologies in our midst, we can certainly still be curious but we should pause before asking ‘How could I use it in my classroom’? We could ask these questions first:

- What is this technology?

- Whose is it?

- Why is it here?

- How did it get here?

- Whose purposes does it serve?

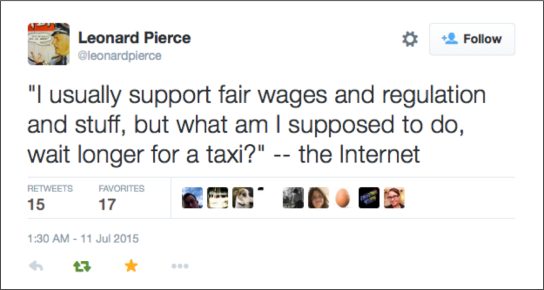

4. Call out bullshit for what it is

I’m using ‘bullshit‘ here as a philosophical term. It comes from the literature and has been used by various scholars, including Ian Bogost and Neil Selwyn. According to Selwyn (2015), Frankfurt describes ‘bullshit’ as

language that is excessive, phony and generally “repeat[ed] quite mindlessly and without any regard for how things really are”. Seen in these terms, then, much of what is said about education and technology can be classified fairly as bullshit. Pursuing this line of critique therefore makes it easier to unpack the problematic nature of the language of education and technology.

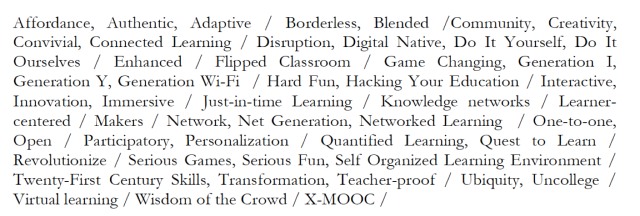

To this end, Selwyn, in a version of his ‘Minding Our Language’ paper no longer appears to be available, provided an “incomplete A to Z of Ed-Tech weasel words and terms that deny different, inequality, hierarchy and hardship”:

Keep an eye and ear out for them and ask yourself: where and/or who do they come from? Are there any connections or correlations, as Selwyn argues, with the dominant ideologies of libertarianism, neoliberalism and new capitalism?

5. Disrupt them back

As Brunton and Nissenbaum (2015, p. 1) describe, there are various forms of ‘obfuscation‘ – “the deliberate addition of ambiguous, confusing, or misleading information to interfere with surveillance and data collection” – which we can use to ‘disrupt’ those who might seek to disrupt us.

You can discover more at Me and My Shadow.

Privacy Tools is another useful site I discovered recently via Scott Ludlam.

Conclusion

Resistance is not futile. We can ‘change our default settings’, both literally and figuratively. We do have options open to us, although, as Phil Howard argues, they may not all remain open for a great deal longer. As Edward Snowden said last year,

you’ve got to figure out what you believe in and stand for it. You have to stand for it…think about the world you want to live in and then be a part of building that.

Part 1: Attitudes to educational technology

Part 2: Educational technology as ideology

Kyle, whenever I read the most recent edition of this I am stunned; at an instinctive level my deep fears are validated. Um…thanks for that…

Your research articulates serious issues and complex problems. How do we find accessible means to communicate these ideas to the masses. The simple claim that “I don’t trust it”, inevitably leaves one (mis)labelled as a luddite, and is unlikely to inspire others to follow.

Thanks for the feedback, Michael. It reminds me of a comment from a colleague a couple of weeks ago: ‘permission to be paranoid’!

I’ve found these issues difficult to understand, talk about and write about – because of the technical and sociological complexities, it’s hard to make a coherent argument without sounding a bit nutty or boring people. But I think there is a growing awareness which will slowly make it easier to discuss, raise concerns and respond in a meaningful way and to resist the ‘weary resignation and uncomfortable compliance’, as Selwyn puts it.

Anyone interested in reading Neil Selwyn’s article ‘Minding our Language’ should be able to access it here: https://www.academia.edu/9792417/Minding_Our_Language_-_why_education_and_technology_is_full_of_bullshit_…_and_what_might_be_done_about_it

Thanks for sharing that, Philip – I should have done that myself 🙂 The published version of that paper sadly doesn’t include the ‘Ed-tech weasel words’ appendix – it was in a version accompanying Selwyn’s presentation of the paper at the ‘Digital Innovation, Creativity and Knowledge in Education’ conference in Qatar in January this year.